Meanwhile, Back in the Old Country

It started with a walk in the woods in the Pacific Rim National Park in coastal British Columbia in 2006. Walking through the lush green canopy of the rain forest, I saw a number of fallen trees, with other younger trees growing out of them, their roots straddling decaying trunks.

It started with a walk in the woods in the Pacific Rim National Park in coastal British Columbia in 2006. Walking through the lush green canopy of the rain forest, I saw a number of fallen trees, with other younger trees growing out of them, their roots straddling decaying trunks.

One memorable scene (for some reason, I didn’t take a photo of it) was a row of small trees growing in a perfectly straight line, each of them bowlegged, and growing out of an invisible giant that had long since disintegrated into empty space.

It struck me that the mother tree had grown, flourished, died and returned to the earth over a period of hundreds of years, never to be seen again, and yet here she was; her ghost clearly visible, her influence still being felt many years into the future.

Writers, composers and architects have of course built or written things that preserve their legacy for future generations. But for most of us mortals, the memory of our time on earth disappears when the last person who ever knew us is finally gone.

Or does it?

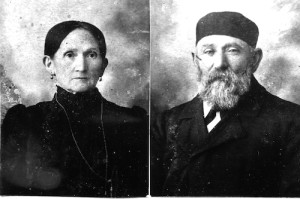

When I think about my grandparents and the world they lived in, and about their parents, and their parents’ parents, I wonder how much of their behavioral DNA lives within me. It could literally be passed down genetically, or I could have just picked it up from the humor and mannerisms of my own mom and dad.

When I think about my grandparents and the world they lived in, and about their parents, and their parents’ parents, I wonder how much of their behavioral DNA lives within me. It could literally be passed down genetically, or I could have just picked it up from the humor and mannerisms of my own mom and dad.

When I pout and shrug my shoulders to imply “who knows,” did that come from me, or is it something I picked up from my mom and her father? How much of my personality comes from a world before my time, from people I never met, who may have wondered about the future the way I wonder about the past?

I stepped out of the woods that day, and stepped into a journey to learn more about the world my ancestors lived in. In the process of searching for them, I hoped to find something of myself. My travels have taken me to countless internet sites, cemeteries from New York to Strasbourg France, Google Street views of Glasgow Scotland, and most recently to the “old country” – a land that doesn’t even exist anymore, at least on the map. The lands of my grandparents have changed borders and flags many times since they lived there – what used to be Galicia, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Russia is now Poland and the Ukraine. In the late 1800’s, nationality in this region was a fluid concept. The Austrian army recognized eleven official languages in which army regulations were printed. But many of my ancestors considered themselves Galitzianers, and in my visit to Krakow Poland last month, I was to my knowledge the first from my family to step foot in the old country in over 100 years.

I didn’t visit the little villages where my family came from on this trip. Some of them are in areas that require a lot more planning to visit than I had time for. Maybe I was afraid of being disappointed if nothing recognizable from the past remained in these towns. So I chose Krakow because it’s well-preserved, and might offer a feel of the world that my grandparents and great-grandparents left behind.

I had all kinds of preconceived ideas about Poland before I went. I read someplace that when we travel, we often look for what we expect to find, especially stereotypes. And we usually find it – whether it be cowboys in Texas, short-tempered cabbies in New York, polite people in England, or babushkas in Poland.

I expected Poland to be backwards, dull and full of cranky people. After all, this is a country that had been overrun by neighboring countries for hundreds of years. For generations, this had become a defining characteristic of Poland. It was a country until the 1700’s, and then divided between Russia, Prussia and Austria. It stayed that way for 123 years, until the end of WW1, in 1919, when it became Poland again – but only briefly. The Nazis invaded in 1939, and destroyed much of its society. The most notorious concentration camps were in Poland. Then the Russians made it a communist satellite state after the war, and finally in 1989 it became an independent country again. The past 20+ years have been a bumpy road, as the country reasserts and builds upon its identity, now as part of the European Union.

I expected Poland to be backwards, dull and full of cranky people. After all, this is a country that had been overrun by neighboring countries for hundreds of years. For generations, this had become a defining characteristic of Poland. It was a country until the 1700’s, and then divided between Russia, Prussia and Austria. It stayed that way for 123 years, until the end of WW1, in 1919, when it became Poland again – but only briefly. The Nazis invaded in 1939, and destroyed much of its society. The most notorious concentration camps were in Poland. Then the Russians made it a communist satellite state after the war, and finally in 1989 it became an independent country again. The past 20+ years have been a bumpy road, as the country reasserts and builds upon its identity, now as part of the European Union.

Between 1890 and 1914, my ancestors, as in Fiddler on the Roof, were forced to leave the villages where they had thrived for hundreds of years, and move to large cities, where they joined others who had been there since the 14th century. Farmers became tailors and furriers. My forefathers were lucky enough to come to America during this time. But by 1939, those who were left had to give up their property once again, and move into the ghettos that the Nazis had created.

By the end of the war, 90% or 3 million of the Jewish inhabitants of Poland were dead. Communism seemed to kill off what was left, through assimilation and conversion to Catholicism, or emigration. Poland became a graveyard of sorts.

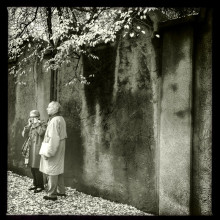

So yes – I did see some humorless people in Poland. I saw the decay of old buildings that have witnessed terror and despair. I saw what I expected to see. Or at least I did on the first day.

———

Stepping into the ghetto in Krakow is like crossing 70 years in an instant. Of course this is only a blip in the life of a medieval city. While some buildings have been restored, many of them seem to be in the condition they were left in after the war. And yet most of them contain vibrant businesses, restaurants, shops and galleries. There are rows of Jewish restaurants. Several synagogues. Klezmer concerts. Tourist shuttles.

But wait a second. This is an illusion, isn’t it? People wanted to see where Schindler’s List took place, and was filmed – but were any Jews actually still around? Was this some sort of bizarre theme village? Did locals pretend to celebrate the city’s past inhabitants, just to capitalize on the commercial draw of tourism? Was this neighborhood left unpainted so that it could be like a quasi-authentic-simulated-faux cultural experience, complete with blintzes and hand-carved rabbi figurines? The Saturday flea market had old SS insignias and German helmets next to silver menorahs and yellow stars of David. I was disgusted and mesmerized, as I struggled for insight.

What I learned surprised me. As I listened to a concert in the old Izaak synagogue (built in 1664), I saw an orthodox rabbi leaving his office, accompanied by a scurry of followers. Posters for various cultural and religious events were stapled to walls around town. There seemed to be Jewish employees in various shops and restaurants around town. That evening when I Googled the topic, I learned that there is indeed a resurgence of Judaism in Poland (30,000 today), and in Krakow in particular.

In addition, many Poles whose parents converted to Catholicism to avoid trouble have learned about their true heritage through the internet, and are suddenly interested in finding out more.

At the same time, anti-semitic graffiti persists.

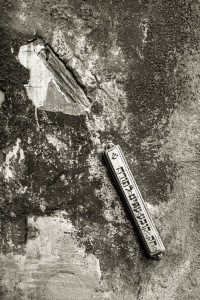

At one point, I saw volunteers cleaning up an ancient Jewish cemetery. The Jewish cemeteries of Krakow were largely destroyed by the Nazis; their stones ripped up, broken apart and used for paved roads. After the war, there were painstaking efforts to return what was left of the stones to their original locations. Pieces that were too small to be put over a grave were assembled as part of the walls surrounding the cemetery.

The walls profoundly moved me, to think that these people who lived not so long ago, were represented now only by little fragments – their names unknown – like the fading memories of a dream when you first wake up and can’t really tell if it happened or not.

The ghetto wall was built in 1941, still exists in 2 spots. It looks relatively new, which is a revelation in itself. It was put up to keep the 15,000 Jews who were still left in Krakow locked inside of 14 square blocks – one apartment for every four families. Ironically, the cement-covered brick panels were built in the shape of tombstones.

It always strikes me when I see the vestiges of the second world war, that it simply wasn’t that long ago. It’s hard to imagine that these walls saw the last 2,000 residents of the ghetto – who were deemed unfit to work in concentration camps – murdered in these streets and in these very houses on March 13th, 1943.

Photographer Unknown. From Jürgen Stroop Report to Heinrich Himmler from May 1943. The original German caption reads: “Forcibly pulled out of dug-outs”

—–

I can’t say “all that aside” because you can’t put it aside. But Krakow is a worthwhile city to visit. Relatively untouched during the war, it boasts one of the largest town squares in Europe. The restaurants are fabulous. The young people are beautiful. There’s music everywhere. This is the city that nurtured Pope John Paul II. It’s the land of Chopin and pierogis.

In my few days there, I kept looking for something familiar; something I would recognize in my behavioral DNA. I didn’t have to squint very hard to imagine what this place felt like only two or three generations ago. I looked into the faces of people who looked like my grandparents. I smelled bakeries in the air, and felt the rumble of ancient streetcars vibrating the pavement. I heard an accordion playing through a dark window with lace curtains. I savored the sounds of a language that has way too many consonants, but is somehow smooth and pleasing to listen to.

In my few days there, I kept looking for something familiar; something I would recognize in my behavioral DNA. I didn’t have to squint very hard to imagine what this place felt like only two or three generations ago. I looked into the faces of people who looked like my grandparents. I smelled bakeries in the air, and felt the rumble of ancient streetcars vibrating the pavement. I heard an accordion playing through a dark window with lace curtains. I savored the sounds of a language that has way too many consonants, but is somehow smooth and pleasing to listen to.

I think I was searching for the spirits of my grandparents, and in finding them, hoped I would somehow find a part of me. But as I sat on a Soviet-era streetcar on my last afternoon, I came to the realization that their spirits don’t live here anymore. I wasn’t sure if I was disappointed or relieved.

When I left, I felt like my brain and my heart were getting pulled in two directions. Maybe it was the hellacious head cold I had during my few days there. Or maybe it was that I couldn’t reconcile the almost-youthful innocence of this new country with the ghosts of the old country.

I saw some things in Poland that chilled my blood. But I also saw a love of culture, a vehement dislike of any form of totalitarianism, hope for the future and respect for the past. I realized that the buildings that had seen sadness and grief also saw life.

I’m not quite sure what I learned about myself during this trip. It took me a few weeks to think clearly about it.

As I flew over the impossibly green and gentle countryside near Auschwitz, and towards Germany and the Alps, I reminded myself that children aren’t responsible for the sins of their parents.

I also wondered if anyone really learned anything from the war.

Meine Shtetele Belz

“So when I recall to myself my childhood years, just like a dream, it seems to me

how does the little house look, which used to sparkle with lights?

Does the little tree grow still which I planted long ago?

Oh oh oh Beltz, my little town of Beltz

My little home where I had so many fine dreams.

The little house is old overgrown with moss.

the little house has old no glass in the windows

the little house is old and the walls are bent

I would surely not recognize it again.”

-Alexander Olshanetsky and Jacob Jacobs

The song has special significance in Holocaust history, as a 16 year old playing the song was overheard by an SS guard at Auschwitz extermination camp, who then forced them to repeatedly play it repeatedly to ease the moods of Jews being herded into the gas chambers.